by Rev. Anthony Cekada

Note : The following article originally appeared on the Rorate Caeli blog on August 31, 2017.

MOST OF Rorate’s faithful followers, whatever their opinion on a whole array of other disputed issues, would no doubt agree that the Church’s great patrimony of sacred music deserves to be preserved, augmented and handed down to succeeding generations.

It was with this in mind that I decided to offer Rorate readers an account of how this process of handing down the musical treasures of the past unfolded in one case in my own experience. It is a story that all those who love good liturgical music will find most encouraging.

Readers who know a bit about my background from reading the Preface to my book, Work of Human Hands, may recall that, during my youth in the late 1960s and early 1970s, I was an aspiring organist and composer of church music.

In a post on my blog several years ago, I mentioned that I tried to revive these talents when I wound up as our parish organist here at St. Gertrude the Great Church in 2009.

In the same post, I told the story of how one of our young schoolboys with a good piano training, Andrew Richesson, had picked up the rather specialized art of organ improvisation on Gregorian themes merely by listening to me improvise. I posted a video of one of his improvisations at age twelve, and another video of him, at age fourteen, confidently blasting his way through the Bach Gigue Fugue, with his feet flying up and down the pedalboard. Andrew’s ability to perform the latter was fruit of his study, beginning at age 11, with a top local organ teacher, Dr. John Deaver, of the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music.

Andrew’s expertise at the keyboard quickly surpassed my own, and he was able to play a variety of technically-demanding and brilliant voluntaries (organ solo pieces), many of which I posted on my YouTube site:

- Boëllmann, Toccata in C minor from the Suite Gothique

- Gigout, Toccata in B minor

- Bach, Toccata and Fugue in D minor (Yes, the “Phantom of the Opera” one…)

- Bach, Toccata in D minor, “The Dorian” — a far more challenging work than the preceding one.

- Buxtehude, Passacaglia in D minor

- Bach, Gigue Fugue in G major, this time performed flawlessly at age 17.

Other works included Vierne’s Carillon de Westminster, selections from Mendelssohn’s organ works, César Franck’s knuckle-busting Pièce héroïque, and one of the fearsome Bach Trio Sonatas, which the Master wrote as exercises to challenge the keyboard skills of his sons.

Nearly all these works served as rousing and noisy postludes played after High Mass, but Andrew also played a wide array of more meditative pieces appropriate to various sections within the rite itself. The traditional High Mass, by the way, provides a skilled organist with more opportunities to play interludes than any other liturgical rite I know of.

Andrew took my place at the organ first for our summer congregational High Masses, then as choir accompanist for major feasts in 2015 and early 2016, and finally last summer, as the parish organist for all choir Masses at St. Gertrude the Great on Sundays and feast days.

The latter, in particular, was providential for our music program, because a bout I had with cancer put me out of action for the better part of a year, and then left me with nerve problems in my fingers and feet.

Andrew also took an interest in composing music. Using the miracle of modern music notation software, which can also produce realistic-sounding audio files, he came up with pieces as disparate as a Beethoven parody and a driving fantasia for orchestra with overtones of the twentieth century composer Carl Orff.

In summer of 2016, at probably the low point in my chemotherapy treatments, Andrew sent me his Mass of St. Gregory the Great — a musical setting of the Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei for organ and three-part chorus. He had composed this work without formal training in musical composition; he merely drew upon what he had absorbed from listening to the wide array of Masses and motets in our choir’s repertory.

He asked for my opinion. I was bowled over by the sound, but since Andrew was on the SGG home team, after all, and since my knowledge of correct formal standards for musical composition had lain dormant for fifty years, I didn’t trust my own judgment to be sufficiently objective. He had put a lot of time into the project and deserved a more balanced and analytical response.

So, without Andrew’s knowledge, I sent the work off to Dr. Peter Kwasniewski and Nicholas Wilton, two composers whose liturgical works are superbly crafted in the classical style and are performed in the traditionalist/Indult milieu. Both sent very favorable and helpful responses.

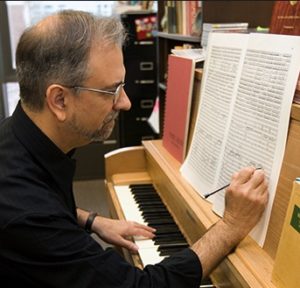

On a whim, I also sent the score of the Mass to Dr. Miguel Ruig-Francoli, Distinguished Teaching Professor of Music Theory and Composition at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music, an internationally recognized composer, and an expert in musical pedagogy and Renaissance polyphony.

Dr. Francoli was not only impressed with the Mass, but also offered to tutor Andrew privately in counterpoint and musical theory, and in the process, to help him revise the work. An outsider to the academic world of professional music might not grasp the significance of this, but an offer of private tutoring from such a distinguished musician is in fact a testimony to a student’s potential talent.

So, from October 2016 to June 2017, Andrew, now 17, studied privately with Dr. Francoli, who taught him how to rigorously apply formal musical standards to the Mass of St. Gregory the Great. The work has been carefully polished and is now complete.

The Mass, which Andrew dedicated to his parents, is within the capabilities of the average choir, and combines the men’s voices into one baritone line. Two sections of the Mass, the Kyrie and the Sanctus, were recently premiered at a concert by a local choir in a Protestant church, with the composer accompanying.

As you can hear, both movements, though relatively short, have a powerful forward “drive” and a rich musical texture, thanks to the overlapping voice lines, that makes them stirring and majestic.

This effect is not the result of chance. Still less, does it merely arise from the composer having “good ear” for a catchy tune, combined with the ability to bang out some nice chords to accompany it.

Rather, those few of us who have actually studied the nuts and bolts of musical composition know it is the result of the painstaking application of the composer’s craft: taking short tunes (motifs), and developing them through variations in rhythm, key, major/minor mode, harmonization, tension, resolution, successive entrances of voices at different pitches, polyphony, homophonic harmony, and all the rest.

These sophisticated methods of musical development all lie under the surface in Andrew’s Mass of St. Gregory the Great, and combine into one harmonious whole, which Dr. Francoli praised as “well-crafted, effective, beautiful and functional.”

Here is the complete version of the Mass in a computer-generated digital sound format:

I invite readers to tell choir directors in their churches and chapels about this remarkable piece of sacred music. It is well within the abilities of most parish choirs, , and deserves to become a standard part of every TLM choir’s repertory, especially for festive occasions.

The full score is available for download from Andrew’s page on WikiChoral (CPDL).

Andrew will major in computer engineering in college this coming Fall, but he will minor in musical composition. So we can hope for many more such compositions that will add to the beauty of the sacred liturgy, not for the sake of art or for the fame of composers and musicians, but soli Deo gloria — for the glory of God alone!

Postscript

I am happy to report that our choir at St. Gertrude the Great Church in West Chester, Ohio, has now recorded the entire work. We premiered it at Midnight Mass on Christmas 2017, and sang it again the following Sunday, December 31.

For the latter occasion, we were honored to have in the congregation Dr. Miguel Ruig-Francoli, who, as noted above, had privately tutored Andrew in composition and helped him polish the final version of the Mass.